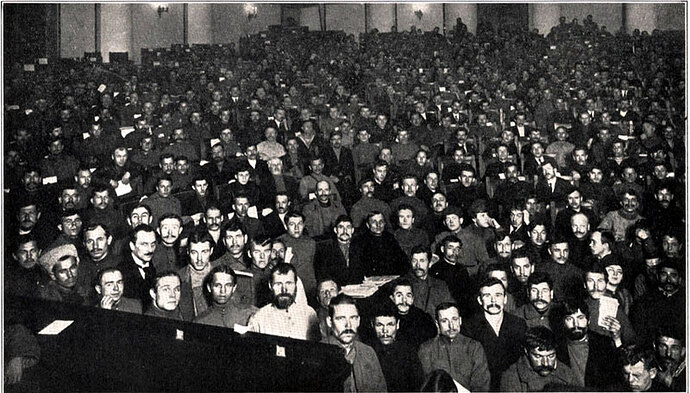

My colleague, Per Månson, is not particularly interested in meetings (at least not as much as I am), he is interested in Russian history (much more than I am). But our interests met when he told me about incredibly important details of a meeting that changed not only Russian history, but arguably world history: the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets which took place in the Assembly Hall of Smolny in Petrograd (today: St. Petersburg) from 25 to 27 October 1917 (Julian calendar, 7-9 November 1917 in today’s Gregorian Calendar).

The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets 25-27 October 1917To learn about the historical significance of this meeting, you can consult any history book with a chapter on the October Revolution (also known as the Bolshevik Revolution).

Julij Martov

Julij Martov

In his blogpost, Per details the dynamics of what he argues were crucial minutes first in the evening of 25 October 1917. If you understand Swedish or don’t mind using Google Translate, you will get the best picture by reading the original text, but the gist of it is the following: When Julij Martov, a Menshevik Internationalist, proposed immediate action to form a coalition government (including all socialist factions), his proposal was met with applause and virtually everyone, including the Bolsheviks, voted in favour of this plan. It is likely that Lenin and Trotsky would have opposed such a broad coalition government, but the reaction in the room showed that they would have not been able to stop it. However, as it turned out, they did not have to worry about that. Because here is how the meeting continued: When Lev Chintjuk, of the Conservative Socialists, proposed that the only way to solve the crisis was to start negotiating with the provisional government, he was booed at and called a bourgeois lackey and the like. Several other speakers endorsing the proposal received the same reaction. Then it was announced that shooting had started at the Winterpalace and some of the right-wing socialists left the congress. When Martov made a final attempt to start the building the coalition government as has been decided just an hour earlier, the room turned against him and rejected the plan.

What had happened? As I understand it, the meaning of building of a coalition government had changed because the right-wing socialists interpreted it as a government of which even bourgeois parties would be a part and that was unacceptable for most of the other delegates. Although this was not Martovs intention and not what had previously been decided, the idea of coalition government had become synonymous with “a coalition government which includes non-socialist parties”).

As Per puts it in his article: “Trotsky could now deliver the final blow to Martovs proposal in this historical moment where the Russian revolution could have taken another path” and, for lack of an audio recording of the meeting, he cites from Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution:

What has taken place,” says Trotsky, is an insurrection, not a conspiracy. An insurrection of the popular masses needs no justification. … and now you propose to us: Renounce your victory: make a compromise. With whom? I ask: With whom ought we to make a compromise? With that pitiful handful who just went out? … To those who have gone out, and to all who made like proposals, we must say, ‘You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your rôle is played out. Go where you belong from now on – into the rubbish-can of history!’”

Leo Trotsky

Leo Trotsky

When Trotsky’s words were met with applause, Martov shouted: “Then we are also leaving”, and he reportedly left the congress in a silence that perhaps indicates some subconscious sense for this historical moment. After the opposition had left, Lenin was able to install his one-party government instead of replacing the provisional government with an all-socialist coalition government which would have represented the vast majority of the Russian people.